Spinoza’s Life – From Vidigueira to Amsterdam

Bento de Spinoza, also called Baruch or later Benedictus, was born in 1632 in Amsterdam, the son of Portuguese-Jewish refugees. His father, Michael d’Espinosa, a son of a wealthy merchant, hailed from Vidigueira, where the family had lived for generations. After the expulsion of Jews during the inquisition in Spain and Portugal in 1492 and 1497, many – including the Spinozas – fled the Iberian Peninsula. They stopped briefly in Nantes and eventually found refuge in the relatively tolerant Amsterdam. The city, since the fall of Antwerp, had become the new maritime and trading centre, and a place where Jewish life could cautiously flourish again.

Spinoza grew up in Amsterdam’s vibrant Jewish quarter, ‘Vlooienburg’, mostly home to Sephardi Jews, who built their synagogues there – the large Portuguese Synagogue still stands today. He was educated in the Jewish tradition, but soon became captivated by the radical new ideas of his time – especially the philosophy of Descartes and the discoveries of emerging science.

In 1656, Spinoza was excommunicated from the Jewish community, likely for his unorthodox views. The ban meant total exclusion – but it also freed him to think and write without religious constraints. He learned Latin, became part of a circle of freethinkers and scientists and supported himself by grinding optical lenses, used, among others, by the renowned scientist and astronomer Christiaan Huygens. Not only his thoughts, but also his lenses, gave people a more profound view on life.

Though cautious about publishing, Spinoza dared to speak out. His Theological-Political Treatise, published anonymously in 1670, was a bold defence of freedom of thought and expression, maintaining close ties with friends and intellectuals across Europe. He lived a modest and independent life, caring more for feeding the mind than indulging the body. Later in life he is said to have sustained himself on raisins and milk-porridge. By some he was called ‘Mister Spinach’, after the leafy vegetable said to nourish the brain.

Spinoza died in 1677 at the age of 44, most likely from tuberculosis. It is believed that his dust-rich optical work, while sharpening lenses, dulled his lungs, and contributed to his declining health. His philosophical work – considered dangerous at the time – was quickly banned but continued to circulate underground. Over time, his ideas helped shape modern philosophy, science, and democracy.

And in some way, it all began here, in Vidigueira, the birthplace of his father – where a radically independent mind took root.

>> Read more about Spinoza's philosophy.

-

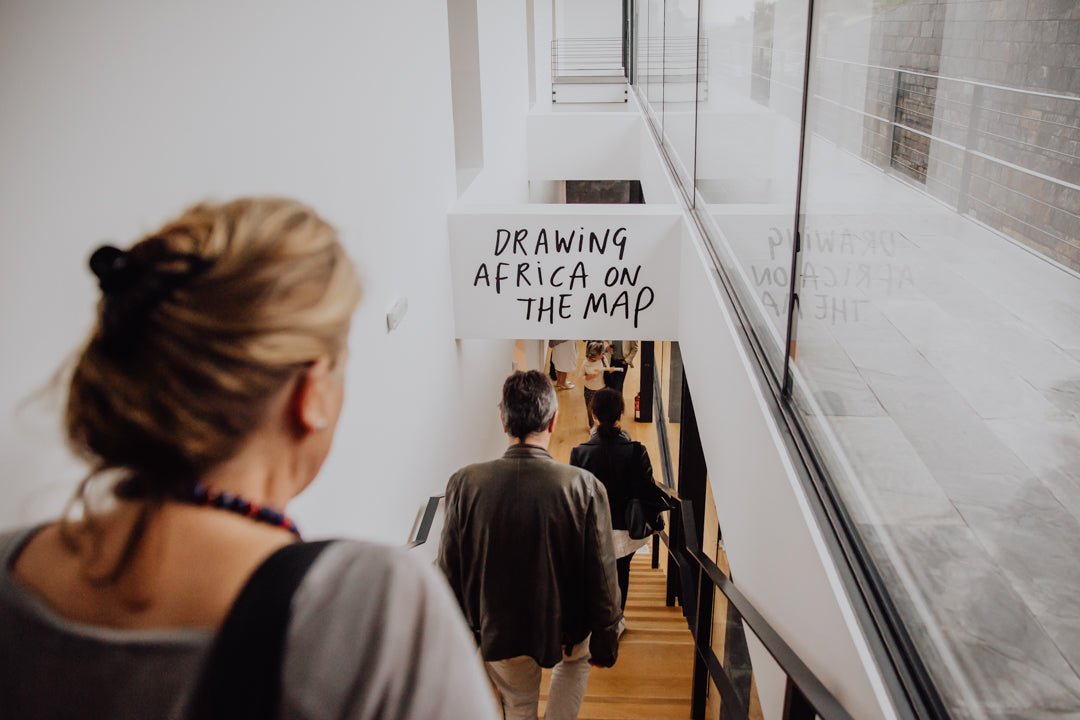

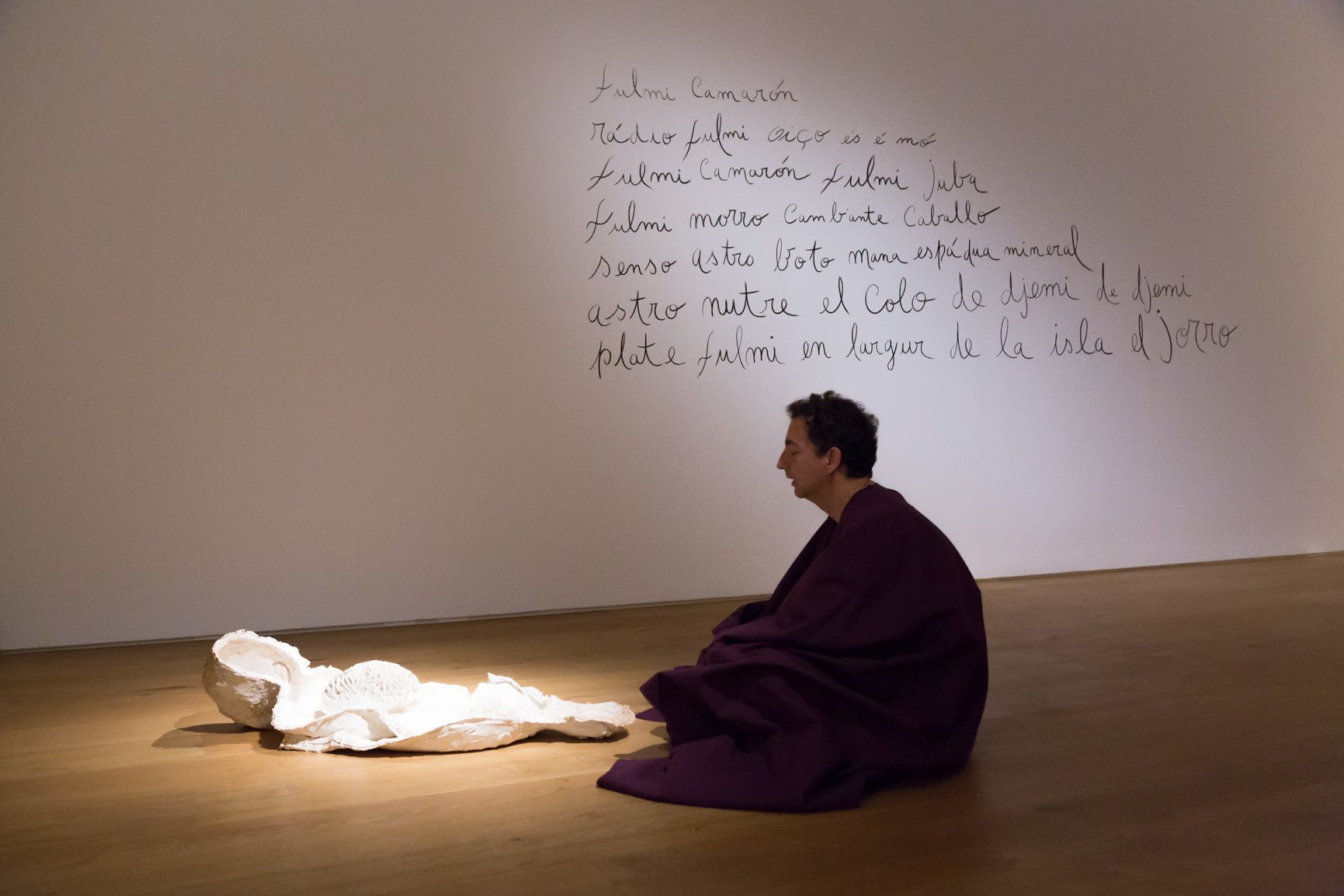

Cristina Lucas

In To the Wild Cristina Lucas reimagines an old method of humiliation and exile. In the practice of ‘tar and feather’ a woman prisoner’s hair is cut, her body covered with tar and then feathers, after which she is paraded through the streets and left outside the city. Once a common punishment, in Lucas’ work the exiling ritual becomes a means of reconnecting to nature and finding one’s place in the natural order of things. An order we can, according to Spinoza, sense with our most direct form of thinking: intuition. Lucas writes that Spinoza’s thoughts accompanied her on her journey of becoming profoundly connected to nature.

Spinoza too was excommunicated from his society: the Jewish community of Amsterdam. His thoughts challenged traditional views on power and religion that lived in that community. Still, he believed that societies are a natural extension of human nature. Just as individuals are indispensable parts of God/Nature, societies are too. They are formed through connection over reciprocal wants and needs. But, obedience to such a society or state should be rooted in reason and common interest, not blind submission.

Though intuition is our most immediate knowledge of the world, Spinoza thought we should use reason to understand the causes behind what we feel or experience. So that we can be freed of a passive life, led by emotions. At the same time, the society we live in can blur our reasoning, making it necessary to break free of its dogmatic thought.

-

Navid Nuur

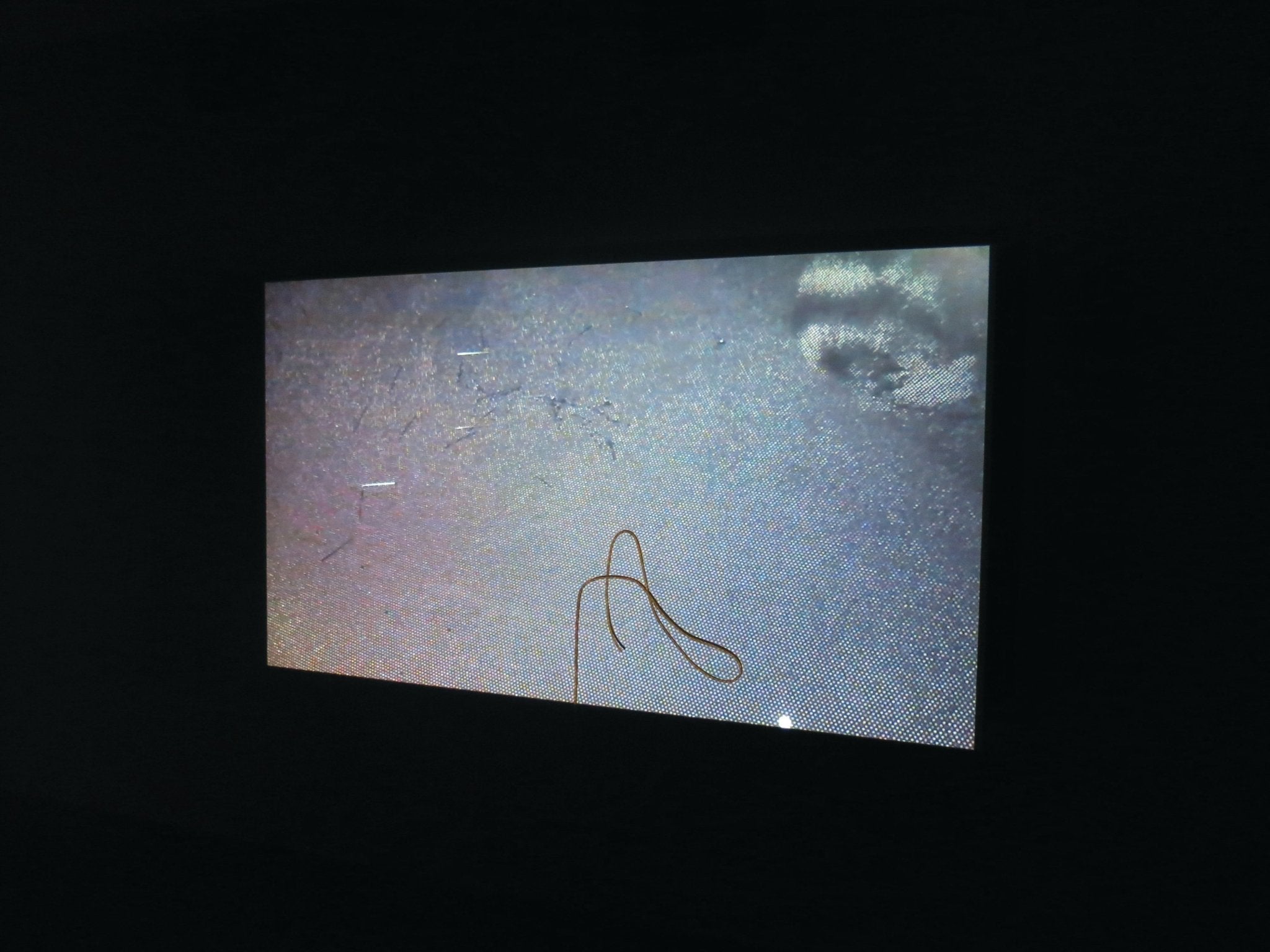

The works of Navid Nuur often engage with natural elements – ashes, light, air, tears – to create experiences that feel wondrous. Some have even called him a modern-day alchemist for blending materials into new substances. Yet, as Nuur himself points out, his art is not esoteric. It, instead, offers a point of departure for reflection.

Spinoza would likely have appreciated Nuur’s work for several reasons. Spinoza rejected the existence of miracles, arguing that what people perceive as wondrous are merely natural, scientific phenomena not yet understood. They also share a deep respect for all material elements as equal parts of a greater whole – none inherently superior to another. As Nuur once said, he sees no difference between working with a human being, a room, a beam of light, or a church.

A final kinship between the philosopher and the artist emerges in Nuur’s work Ours, which features a microscopic image of a human tear – presumably his own. Up close, the dried salt has crystallized into tiny, landscape-like formations. The tear becomes a world in itself. In a letter to Henry Oldenburg, Spinoza uses a similar metaphor to explore perspective. He imagines a bloodworm living in a drop of blood, perceiving the small particles of it as a self-contained reality. The worm, due to its limited view, is unaware it exists within a larger body.

Likewise, when we examine a tear through a magnifying lens, we uncover crystals, bacteria – invisible to the naked eye. What seems simple becomes complex, depending on the perspective and tools we use. If we forget this, we won’t ever understand the true nature of the world. For in our complex and connected world everything depends on everything else and nothing truly belongs to just one of us; it is instead all Ours.